Teresa in her turn describes

Valle in chapter XXIII as a «mago fakir antes de Cristo»

and refers to his Lámpara maravillosa: «Sobre

mi mesa se

abrieron como brazos en la sombra las páginas de la

lámpara maravillosa de Don Ramón María del

Valle-Inclán» (apud Hormigón, Biografía:

757 ). (On my

table the pages of La lámpara maravillosa of

Don Ramón

María del Valle-Inclán opened like arms in the shadows").

She mentions his

cape. «Pasó, su luenga barba

hacía

compás al vuelo de su capa inflada.» (He

passed by, his

long beard keeping rhythm with his inflated cape). Teresa herself wore

a black

"capelina” or small shoulder cape which her daughter Sylvia describes

her wearing

in her memoirs. (Schiavo"mujeres":255)

González

Vergara tells us that Valle accompanied Teresa on a trip to Avila and

Toledo

without specifying a date other than in June of 1918. Edwards claims

that

Teresa was very moved by seeing the city of her namesake and said she

wanted to

spend her last days there (Schiavo «mujeres»:253).

The

collection of poems that make up El

pasajero was first published the 15th of February, 1920, one year

before

Teresa's suicide in Paris on December 24, 1921.

Teresa

was displaying self-destructive tendencies during her first visit to

Madrid

according to Edwards, who said to Cansinos Assens in his tertulia in El

Café

Colonial: «Esta Teresa se está arruinando la salud, bebe,

toma coca, se pincha.

¡Es un dolor! (apud Hormigón

Biografía: 757) (Teresa is

ruining her health, she drinks,

she takes cocaine, she injects herself[with drugs].

It's dreadful!) Teresa had attempted suicide once before while

confined to the convent in Santiago in 1916. That

time she took an overdose of morphine. In

Paris she took veronal which according to

Cela's Mrs. Caldwell Speaks with Her Son)

is a suicide "de buen tono" : "siempre fue de buen tono, hijo,

debe tomarse con champán y por la noche. " (apud. Muñoz Coloma «La

Patrona») (“[Veronal] was always in good taste, son.

It should be taken at night with

champagne")

The

1920 edition of El Pasajero is the

only one which is divided into sections which include Tentaciones."

(Temptations).

Several of the poems there appeared in June coinciding with the time

that Valle

and Teresa were on their trip through Castilla. One of them titled

«Rosa del

caminante», was first published in El

Imparcial, as «Ciudad de Castilla: rosa del camino»

(June 3, 1918) Besides

the cities mentioned in the last verse: Astorga, Zamora and

León, the poem

seems to refer to Toledo, the Castilian city, emblematic of death and

the

ravages of time in La lámpara. Just

as in that work, the 1920 edition of El

Pasajero presents Galicia as the contrary of Castilla.(for the

importance

of "contrarios" or contraries), see Garlitz, Andanzas

) «Rosa matinal», originally titled “del Celta es la

Victoria," (dated 13 August 1918) contrasts the "parda tierra

castellana"(the brown Castilian earth ), "with the freshness and

vitality of Galicia. "el verde

milagro de una tierra cristalina"

(the green miracle of a crystalline land).

"Rosa del paraíso...,"

also published in June (El Sol, June

9th) under the title of "Rosa del

mito solar," seems to continue the description of Galicia.: "El campo

verde de una tinta tierna,/Los montes mitos de amatista opaca." (the

earth a tender

tint of green/the mountains, myths of opaque amethyst").

In La

lámpara, the narrator connects himself with Toledo by

describing the

portrait that El Greco painted of Cardenal Tavera based on his death

mask and

implying that his own true face will be revealed in the "último

gesto" or last gesture, that death will make visible beneath his

mask. One of Valle's first mentions of

a similar mask appears in his lecture "Los Excitantes," which he gave

only once during his 1910 South American tour probably because his

revelations

of personal experience with hashish were considered so scandalous (for

the

complete review of the lecture, which does not appear in Joaquín

and Javier del

Valle-Inclán's collection of Entrevistas

conferencias y cartas, see Garlitz, Andanzas). In that lecture,

Valle describes the feeling,

induced by hashish, of a wax mask formed

on his face ("en su rostro sintió algo que era la

sensación exacta de una

máscara de cera puesta en él") ( "he

felt the exact sensation of a mask of wax [being] placed over his

face").

In

1918 Valle was only 52 but he must have felt like a very old man, close

to the

revelation of his "último gesto," in the presence of the 25 year

old

"tentadora," Teresa.

In

1918 Valle was only 52 but he must have felt like a very old man, close

to the

revelation of his "último gesto," in the presence of the 25 year

old

"tentadora," Teresa.

Her

friend, Edwards, who observed the two

in a late night session in the Gato Negro café, smoking hash and

writing at the

same table and later at a unsuccessful dinner party [Teresa ruined the

food],

at the home of either Anselmo Miguel Nieto or of Romero de Torres, both

of whom

painted portraits of Teresa, said they were more like father and

daughter than

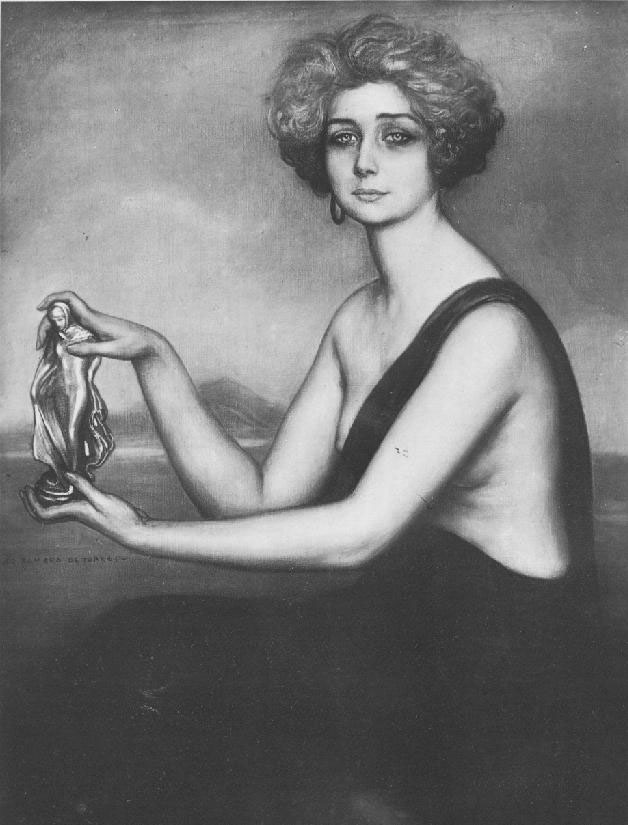

lovers (Schiavo «mujeres»). The portrait by Romero de

Torres shown in

Hormigón's Biografía (754) is the one

that the artist exhibited in his 1922 exhibition in Buenos Aires (see

Santos

Zas «De puño»). I have

not been able to

locate Nieto's portrait.

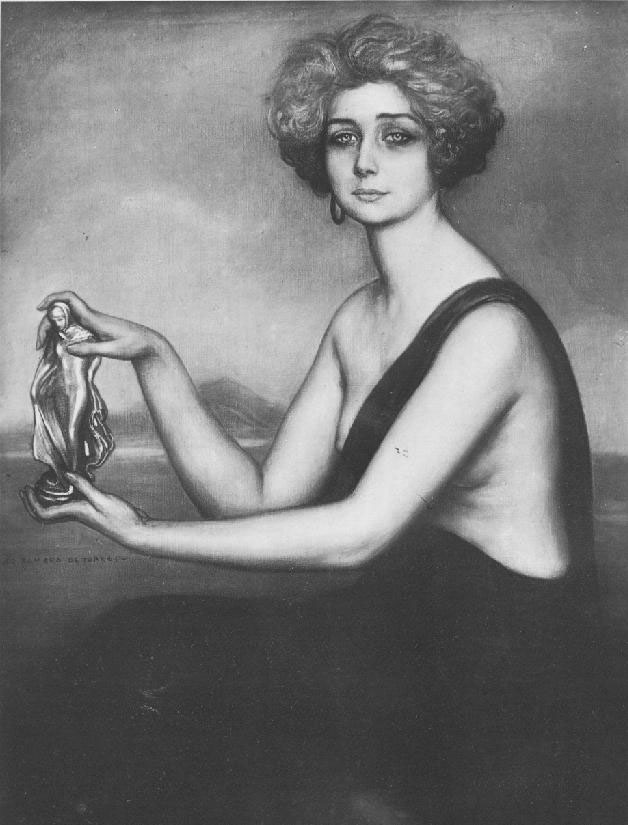

Ortega Pareda ("Patrona")

notes the existence of another oil portrait of Teresa by the renowned

Hispanic-French

portraitist, Antonio de la Gándara (1862-1917) in the Museo

histórico

Palmera Romano in Limache, Chile.

There is a mystery

surrounding the date of the painting. It is given as 1918, but when

Teresa was

in Spain that year, Gandara had already died. Could

it have been done before Teresa left South America? She

does not

look like a femme fatale here.

Ortega Pareda ("Patrona")

notes the existence of another oil portrait of Teresa by the renowned

Hispanic-French

portraitist, Antonio de la Gándara (1862-1917) in the Museo

histórico

Palmera Romano in Limache, Chile.

There is a mystery

surrounding the date of the painting. It is given as 1918, but when

Teresa was

in Spain that year, Gandara had already died. Could

it have been done before Teresa left South America? She

does not

look like a femme fatale here.

Although

Edwards describes Valle's

relationship with Teresa as that of a father and daughter, both

Hormigón and

Schiavo are convinced that something more serious was going on. In fact, Schiavo makes a good case for reading

Clave 1 of Pipa as a love poem to

Teresa.

I

would go so far as to say that the whole group of poems published

during

Teresa's first stay in Madrid (Feb to

Nov. 1918) could be read as a love story

or at least a record of Teresa's inspiration in Valle's work. In his

typical

fashion, don Ramón uses his writing dedicated to another person

as an

opportunity to present some of his personal ideas on aesthetics. (For

example,

in his essays on the National Expositions of Fine Art in 1908 and 1912. See Garlitz, El centro).

If

we see Clave I of Pipa as the

culmination of the group we can then trace the images and ideas

expressed there

in the poems leading up to it. Several of the poems are also connected

to

images and concepts from La lámpara,

published in book form two years earlier. They are a celebration of

Teresa's

youth and her effect on the speaker in the poem: In

"Clave 1", his muse is "la

niña primavera" (the Spring girl), the "Princesa,"

corazón de

abril". (Princess, Heart of April ) who takes him back to the days of

his

childhood when the world had the grace of morning. She

makes his senses sing in the heart of

crystal blue. She moved the "rose

of his heart."

A possible allusion to Teresa as

Princess

April can be seen in «Rosa de mi abril», published in El Imparcial, August 19th 1918. It describes a long ago

love of

the speaker's youth found in a blue garden in April who guides him now

on a new

path. We note that «Rosa de abril» is the title

given to

the Virgin of Montserrat in Jacinto Verdeguer's(1845-1902)

art song «Virolai». (1880).

«Rosa

de furias», later published as «Rosa del destino» (El Imparcial, 24 February, 1919) seems

to elaborate on the line in Clave I: «Y jamás le nieguen

tus cabellos de

oro, jarcias a mi barca, toda de cristal» (And your golden hair

never refuses

[to be] the rigging on my crystal boat"). It describes his ivory boat sailing

under a full moon in April. The speaker might

refer to the impact of Teresa in his life in the line: «Y era

abril cuando

ululante /Por mi vida pasó un ciclón» ("and it was

April when a howling

cyclone passed through my life").

In Clave

I, the speaker calls his muse his

“spirtu gentil". This reference to Donizetti's most famous aria from La favorita (1894) reflects Teresa's

passion for opera (a passion which first

attracted her to her husband according to González, Canto).

The title of the aria which means “Spirit of Light"

could refer to a shared interest of Valle and Teresa in the importance

of light

and especially the sun in its esoteric associations(see

Fernández Ripoll for

the importance of light in Valle-Inclán). This association is

repeated in the

line "En la risa joven del Numen Solar". ("In the young smile of

the solar diety").

In Valle's prologue to Anuarí, he repeats a Gnostic theme from La lámpara that it is this sacred light that

inspires fallen man to

return to it: «El barro recuerda la hora en que salió del

caos ...Con el dolor

de la caída se junta el anhelo por volver a la luz.» ("The

clay [man's earthly form] remembers the hour when it came out of chaos. The sorrow of the Fall is joined with the

desire to return to the light [the divine center of the Great All]).

«Rosa del sol» first published in El

Sol October 13th, 1918 as «Rito juliano» is a hymn to

the sun in its

esoteric meaning as the light which illuminates Eternal Ideas in the

mortal

vessel, or man, through the song of his mouth, that is poetry. In its form as poetry this light redeems the

earthly rock by causing it to transcend into crystal, meaning it

transforms

crass physical form into crystal, or pure substance. «Sacro Verbo

métrico

redime a la Roca del Mundo. Su estrella

transciende al Cristal» (holy metrical word[that] redeems the

rock of the world

and makes it transcend into crystal")

The reference to the Emperor Julian in the original title of

this poem

is elaborated on in the very complex, «Rosas astrales» (I

don't have a date of a

previous publication; 1920 may be its first). There,

the Emperor as the Apostate who denied Christ by

returning to the

pagan worship of the sun is seen as the first to perceive the power of

the

stars(astros) in the creation of poetry. The

poem calls stars or small suns the keys to the Great All.

They

contain the power of the Demiurge, or the Gnostic god of creation, who

like Valle’s

Alexandrine rose in La lámpara represents

the type of art in which the artist views the world from a distant and

dispassionate perspective. I see the poem «Rosa

gnóstica», first published as

"Credo" in El Liberal,

November 11, 1912 as a condensation of that artistic "creed"

expressed in La lámpara. (see Garlitz

«La peregrinación»).

A poem first published in El Sol on

June 9th 1918 under the title of «Rosa del mito solar»

carries as its epigraph a

verse from Darío which is repeated later in the poem: "era el

cielo

cristal", canto y sonrisa" ("the sky was crystal, song and

smile")

This poem becomes «Rosa del paraíso» in

1920. It might refer to an earlier

excursion of

Valle and Teresa, maybe in April. It

refers to Palm Sunday and we know that in 1918 Easter fell in April:

«Esta

emoción divina es de la infancia cuando felices el camino

andamos. /Y todo se

disuelve en la fragancia de un Domingo de Ramos» ("This divine

emotion is

that of our childhood when we walked happily along the road And

everything

dissolves in the fragrance of Palm Sunday")

González

Vergara knows of a letter from Valle to Teresa in which he addresses

her as «preciosa

cristal».

Crystal is a very important

element in Valle's

aesthetic theory which he works out in La

lámpara( see Garlitz el centro,

Schiavo"cristal", and LoDato, All

that Glitters")). In that work, the narrator connects the crystal

with

another of Valle's essential symbols: the rose.(see Garlitz El

centro and Hormigón, Biografía:762)

Could it be that Teresa,

the precious crystal is also the rose? In Clave 1 of Pipa,

"she" is the rose and "he" is the

bull. Maybe that would mean that Teresa

could be the main muse for the «Poemas de las rosas» which

is the first title

that Valle gives to the collection that was to become El

pasajero.

That

title applied to his poetry first appears in El Imparcial

in the series «Las rosas pánicas», on June 10th of

1918.

In

1915 Valle published an essay titled "Las tres rosas estéticas"

which

he later integrated into La lámpara (see

Garlitz «La evolución») .There, the third rose is

the rosa "alejandrina”,

the same adjective that Valle uses to describe Teresa's voice in his

prologue

to her Anuarí which I think helps

prove that Teresa is the «cortesana of Alejandría»

as we will see below. The

Alexandrine rose in La lámpara refers

to Valle's 3rd artistic path or “Gnostic" art in which the artist

observes

the world from above in a dispassionate distanced way as

we saw above in «Rosa gnóstica» (see

Garlitz "El centro and "El

ocultismo") This will be the perspective of what some consider to be

Valle's most important contribution to Spanish literature, that is the esperpento.

Crystal

is also connected to another image, which is key in all of Valle's

work, that

is the mirror. (see, for example Zahareas and Cardona

El esperpento)

In

the poem «Asterisco», originally called «La

Gata» (El Imparcial,October 9,1918 ), a woman conjures the devil, in his guise as Belial,

in a magic mirror."

Instead of Belial ,the mirror reveals,

as in Plato's cave (another of Valle's key

images, (see Esteve "Aproximación"), the real world

behind

the illusory one of the physical senses. The

woman-cat who invokes the devil with her fingers in

"circumflex" is reminiscent of the mother in «Mi hermana

Antonia» whose hand missing the two middle fingers is in a

permanent

"circumflex", that is the sign of the devil's horns. Valle

republished that story on February

21st, 1918. And we remember that Teresa wrote her own poem addressed to

"Beelzebuth, the "Lord of the flies" [a fly appears in Valle's

poem.: «La mosca que vuela busca en el reflejo del cristal, la

mano puesta en

circunflejo»:-("The fly in flight searches, for the hand formed

in circumflex

in the reflection of the mirror.") In 1920

This poem is followed by «Rosa de

Belial», published much earlier as «El íncubo»

(El Imparcial, April 20, 1914), probably because it

refers to the

same form of the devil as Belial, here the incubus who ravishes a young

woman

in her sleep. In her diary, Teresa describes her own mirrors, which

appear in

the magic number of nine: «cuando iba a entregarme al

sueño,me di cuenta que

estaba rodeada de espejos. Encendí

la lámpara y los conté. Son nueve. El hondo silencio

extiende su cristal opaco

dentro del alma» .(Páginas de mi diario

Londres 16 octubre, 1919: 22).

(When I was about to fall asleep, I realized I

was surrounded by mirrors I turned on the lamp and I counted them.

There are

nine of them. The deep silence extends its opaque crystal into my

soul") We

note that there are exactly nine poems in each of the four sections of El Pasajero, (for the importance of

symbolic numbers in La lámpara and

other of Valle's works, see, Garlitz El

centro)

In

his prologue to Anuarí Valle calls

Teresa a «druidesa» and her

voice «alejandrina». The poem titled «Cortesana de

Alejandría» in El Pasajero

(1920) echoes that association. I don't

have the date of its first publication; this may be its first.

Cortesana

de Alejandria is the subtitle of Anatole France's scandalous

(1890) novel,Thaís. It tells the story of a

devout

Anchorite hermit, living in the desert who converts a

young, beautiful, blond, and light -eyed

courtesan to Christianity, only to be seduced by her

in his turn. (It is interesting to note that

one of the critics who commented on his work while Valle was in

Asunción in

1910 compared the morality of don Ramón' s work to that of

France's novel.( see

Garlitz, Andanzas)

Might

the reserved older author, now "exiled" from Madrid in the

"desert" of Galicia who had hitherto, as far as we know, been

faithful to his wife and his life as a father, see a parallel in his

relationship with the seductress Teresa who is blond and light-eyed

like Taís?

The last line of the poem is telling in this regard:"Antonio el

anacoreta

huyó de tu sombra por Alejandría. ¡Antonio

era Santo! Si fuese poeta?..". ("Antonio the

Anchorite fled from your shadow through Alexandria. Antonio

was a saint. [what] If he had been a poet...? "

In

the poem, the cortesana is described as being «docta en los

secretos de la

abracadabra» and the speaker associates her with the serpent, the

rose and

fire, a reference to a reading of Tarot cards inferred by the line:

«dispersó

en el aire tus letras, mi mano». (my hand dispersed your letters

in the

air") The serpent, of course, refers

to the evil tempter in the Garden of Eden. which is constantly

represented as a

woman in the art of the 1890s for example Flaubert's Salammbo

and the paintings of Pre Raphaelites, Waterhouse and

Rossetti,(see Edwards). We have already commented on the importance of

the rose

and we note here that in Clave I, the rose is "encendida"(on fire),

In

the poem, the cortesana is described as being «docta en los

secretos de la

abracadabra» and the speaker associates her with the serpent, the

rose and

fire, a reference to a reading of Tarot cards inferred by the line:

«dispersó

en el aire tus letras, mi mano». (my hand dispersed your letters

in the

air") The serpent, of course, refers

to the evil tempter in the Garden of Eden. which is constantly

represented as a

woman in the art of the 1890s for example Flaubert's Salammbo

and the paintings of Pre Raphaelites, Waterhouse and

Rossetti,(see Edwards). We have already commented on the importance of

the rose

and we note here that in Clave I, the rose is "encendida"(on fire),

Another

poem published during Teresa's first visit in 1918 as «Rosa de

luz» (September

1st in. El Sol) becomes «Rosa de

Turbulus» in 1920, Clave II of the “Tentaciones"or Temptations

section. At first glance, it seems to echo

Valle's Sonata de estío in its description of a

Mayan princess in a tropical setting. Maybe

this is yet another allusion to Teresa who is exotic

since she is

from South America and is as unattainable as a princess by being a much

younger

woman, more like a daughter than a lover .(Cansinos Assens describes

her as

being aloof even though Lasso de la Vega calls her a nymphomaniac) We can connect her to Teresa by the fact that

she fans herself with a rose and that

she recites April verses from her

hammock which has "cadenciosa curva de opio"(the cadenced curve of

opium") The poem also refers to the

red of her lips as being painted with the red flame of temptation

(which

recalls her painted lips noted

by Cansinos Assens) and her hips are the anagram

of the

serpent (see photo ffor a possible inspiration for this image).

According

to González Vergara (El canto),another of

Valle's letters to

Teresa refers to her as "Niña Chole" the young woman in Sonata de estío who is seduced by her

father.

Another

novel of the Sonata series which involves an incestuous relationship, Sonata de invierno was re published on

July 7th, 1918.

The

last poem published in 1918 that might be connected to Valle's

relationship

with Teresa was published the 4th of November of

1918 (that is after Teresa had left Madrid the first time)

in El Imparcial as

«Rosa de bronce», and

becomes «Rosa del rebelde» in 1920. Could the last line «La casa profané con mi lascivia»

(I

besmirched my house with my lasciviousness") express

don Ramón's repentance for his relationship with Teresa?

Of course all this is pure conjecture at this

point. We will have to wait for González

Vergara to find and publish the two letters from Valle to Teresa she

refers to

as well as another of Teresa's diaries she claims to know of. (Hormigón thinks the letters might have

been sent during Teresa's second stay in Madrid, when she and Valle

were unable

to see each other since he was in Galicia at the time.Biografía:791).

As well as for further research on a woman who may

be well be the last muse of the Marqués

de Bradomín, that is Teresa Wilms Montt.

©

Virginia Milner Garlitz

2010

WORKS CITED

Amor y Vasquez, José, «Valle-Inclán

y las musas: Terpsícore», In Estudios

sobre el teatro antiguo hispánico y otros ensayos: Homenaje a Wiliam L. Fichter, A.

David Kossof, José Amor y Vásquez, eds.Madrid: Castalia,

1871.: 11-33.

Cardona,

Rodolfo,Anthony N, Zahareas, Visión del

esperpento Madrid:Castalia,1970(2a edición revisada,1982).

Domínquez

Carreiro,Sandra. «Una mujer olvidada», Anales

de la literatura española contemporánea. (June 22, 2003):

183-204.

Edwards, Meghan. «The

Devouring Woman and

her Serpentine Hair in Late Preraphaelitism», English/History of

Art, Brown

University, 2004. http://www.victorianweb.org/painting/prb/edwards12.htmlEdw

Esteve, Patricio.

«Aproximación al platonismo», Cuadernos

del Idioma 6 (octubre, 1966):39-64.

Fernández

Ripoll,

Luis Miguel «Breve aproximación al símbolo de la

luz en La lámpara maravillosa»

In

Manuel Aznar y Manuel Rodríquez(eds.) Valle-Inclán

y su obra. Actas del Primer Congreso Internacional

sobre Valle-Inclán (Bellaterra del

16 al 20 de

noviembre de 1992). San Cugat del Vallès:Cop d'Idees Taller

d'investigacións Valleinclanianies,1995:179-195.

Garlitz,VM, Andanzas

de un español aventurero por las

Indias .El viaje sudamericano de Valle-Inclán en 1910,

Barcelona: PPU, 2010.

_____.El

centro del círculo. La lámpara

maravillosa de Valle-Inclán.Cátedra

Valle-Inclán Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, 2007.

-------. El

centro del círculo. La lámpara

maravillosa de Valle-Inclán. disertación doctoral,

leida en la Universidad

de Chicago, 1978.

_____.

«La evolución de La lámpara

maravillosa», Hispanística XX 4(1986):193-216.

_____.«La

estética de Valle-Inclán en La media

noche y En la luz del día», Revista de Estudios

Hispánicos (University of

Alabama) XVI (1989):21-31.

_____. «La lámpara maravillosa: Humo y luz» in

Valle-Inclán: El Estado de la Cuestión". Santos Zas ,

Margarita

(coord.)"Estéticas deValle-Inclán". Insula

531(marzo, 1991:11-12.

_____.«El

ocultismo en La lámpara maravillosa

de Valle-Inclán» In Clara Luisa Barbeito(ed.) Valle-Inclán,

Nueva

valoración de su obra (Estudios críticos en el

cincuentenario de su muerte)

Barcelona: PPU, 1988, 111-124.

_____.«La

peregrinación en La lámpara maravillos»"

y El Pasajero En Paulo G. Caucci von

Saucken )(ed.) Saggi in onore di Giovanni

Allegra, Perugia:Universitá di Perugia ,1995:317-324.

González-Vergara,

Ruth. Teresa Wilms Montt. Un canto de

libertad y Libro del camino. Santiago de Chile: Grijalbo, 1993.

Hormigón,

JuanAntonio.(ed.) Valle-Inclán: Biografía

cronológica,

y epistolario

Volumen I (1866-1919). Madrid:

Publicaciones de la Asociación de

Directores de Escena de España, 2006.

Lavquen.

Alejandro «La que murió en París» en Punto

final, no. 540 (March 28, 2003) and

http://lavquen.tripod.com/teresawilmsmontt.htm

Lima, Robert. «The

Gnostic Flight of

Valle-Inclán» in Neophilologos vol.

78, number 2 April(1994): 243-250.

LoDato. Rosemary C. Beyond

the Glitter. The Language of Gems in modernista writers. Rubén

Darío, Ramón del Valle-Inclán, and José

Asunción Silva. Lewisburg: Bucknell

University Press London: Associated University Presses, 1999.

Monge, Jesús

Mª. «"Rosa

de llamas”: Valle-Inclán y Mateo Morral en la revista Los Aliados» http://www.elpasajero.com/MATEOMOR.htm.

Muñoz Coloma,

Luis.«Teresa Wilms Montt. Santa Patrona (Matrona) de los

artistas»,

http://munozcoloma.blogspot.com/2007/05/tereswilms.html.

Ortega Parada,

Hernán. «Teresa Wilms

Montt», http://letrasiberoamericanas.ning.com/forum/topics

Santos

Zas, Margarita. «Valle-Inclán, de puño y letra:

Notas a una exposición de Romero

de Torres» Anales de la literatura

española contemporánea 23(1998):405-50.

Schiavo, Leda,

«Valle-Inclán

y las mujeres itinerantes» Anales de

literatura española contemporánea 279(2002):249-264.

______.

«Reelaboración de

imágenes tradicionales en la

poesía de Valle-Inclán.”“el cristal"» en

La Chispa '93: Selected Proceedings

.Ed. Gilbert Paulini.New Orleans :Tulane University,1993. 327-34.

Wilms Montt,

(Teresa de la+ o Teresa de la Cruz). Anuarí. Madrid: M. Martínez de Velasco,

1918.

_____. Un canto de libertad y Libro del camino:

Obras completas. Ed Ruth González-Vergara.

Santiago de Chile: Grijalbo, 1994.

I

wonder if more of the poems in that collection might have been inspired

by

other "tentadoras" or temptresses. I am

thinking particularly of Teresa Wilms

Montt.

In

1918 Valle was only 52 but he must have felt like a very old man, close

to the

revelation of his "último gesto," in the presence of the 25 year

old

"tentadora," Teresa.

In

1918 Valle was only 52 but he must have felt like a very old man, close

to the

revelation of his "último gesto," in the presence of the 25 year

old

"tentadora," Teresa.